The Simple Shapes of Great Stories, According to Kurt Vonnegut (And Science)

The most brilliantly simple storytelling framework you'll ever encounter.

When I was 15, I fell in love with an 80-year-old man who lived in Midtown Manhattan. His name was Kurt.

I never actually met Kurt, even though he lived just 15 miles from me across the Hudson. But I was obsessed with his stories. I read 27 Kurt Vonnegut books that year, and they made me want to become a writer.

A few years later, I was a senior at Sarah Lawrence College, in that insufferable stage after reading too much Hemingway where you believe that being an alcoholic makes you a better writer. One hazy morning, I discovered a gem on early YouTube: a lecture by Vonnegut outlining the universal shapes of stories that people love the most. It is delightful — a masterclass in storytelling that’s brilliant in its simplicity.

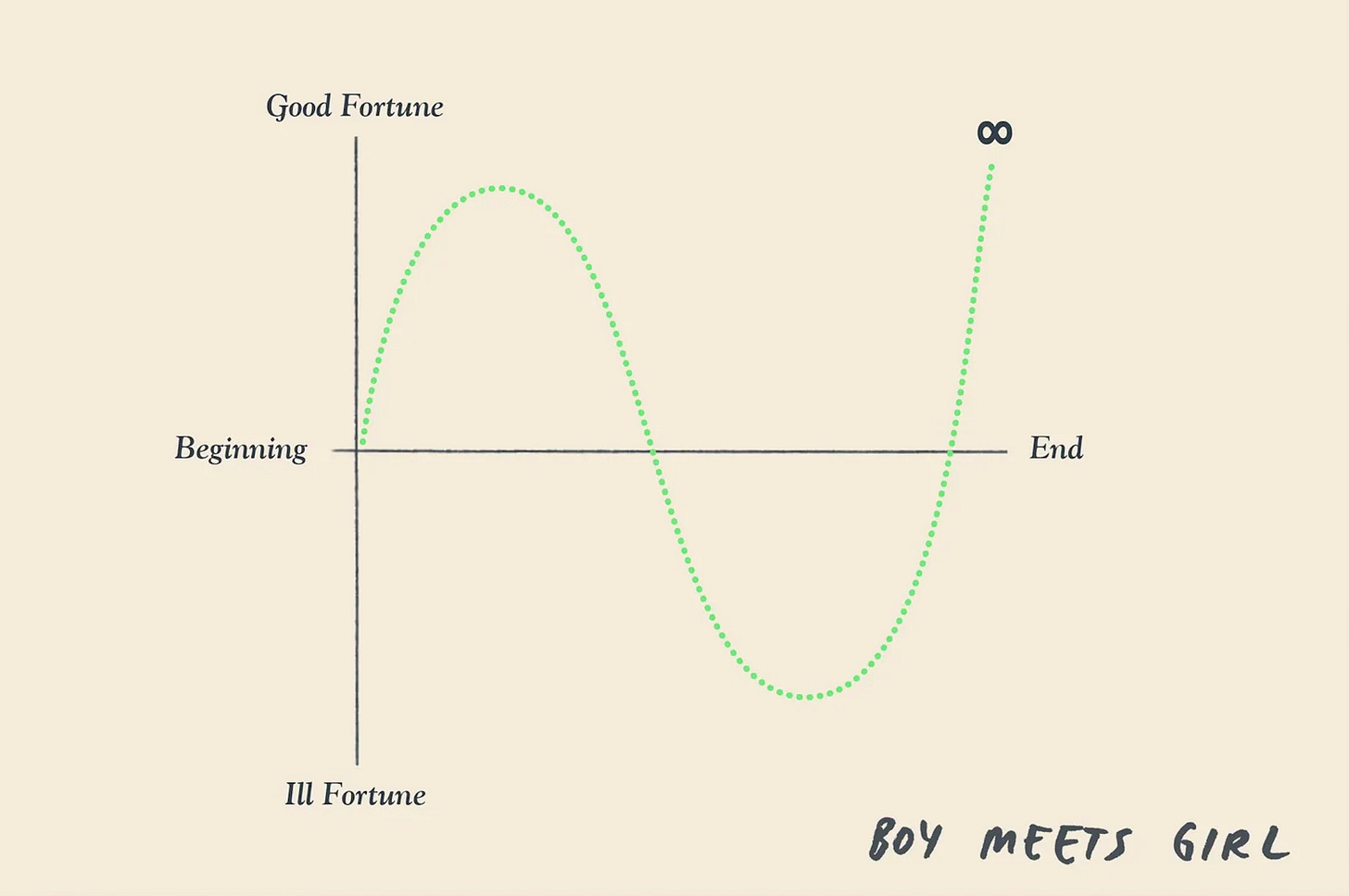

Vonnegut’s story graphs sit on two axes. The X-axis runs from beginning to end. The Y-axis runs from good fortune to bad fortune. If you want to explore all of them, I build a simple interactive tool where you can cycle between the different shapes. And I’d love to go deeper on a few of my favorites:

Man in a Hole

Man in a Hole — “a story we can’t get enough of” — looks like this. Someone living a good life runs into serious trouble — the hole — and needs to get out of it.

We love this story. It’s Finding Nemo, Jane Eyre, Die Hard, Rocky, and The Old Man and the Sea.

This is also the favored structure of viral founder stories — from Apple’s Steve Jobs to Spanx’s Sarah Blakely. And it’s often used for evil, which is why you’ll see a lot of insufferable X threads and LinkedIn broems like this:

Boy meets girl

Boy Meets Girl — the plot of most every rom-com ever — follows a similar pattern to Man in a Hole. The protagonist meets their dream partner, experiences momentary bliss, screws everything up, and then fights for redemption and wins. This plot is 95% of Netflix’s holiday programming strategy, and it works. The top movies on Netflix right now are The Merry Gentleman and Hot Frosty. (What? Yes.)

One important caveat: Boy Meets Girl doesn’t have to map to a romantic story. It can be about achieving any sort of goal, with setbacks along the way.

Then there’s the most popular story in our civilization — the one where “every time someone tells it, they make a million dollars,” according to Vonnegut — Cinderella.

In the Cinderella arc, a character starts in deep misfortune and receives a series of gifts from a deity (ex. fairy godmother) that propel their fortune upwards, only for it to come crashing down (the clock strikes midnight) before they live happily ever after.

As Vonnegut recognized, this is also the story shape of the most powerful tale of all time: the New Testament. It’s also the arc of the second most powerful story of all time: Magic Mike.

Finally, let’s hit the story shape that stirs the repressed goth kid inside of all of us: From Bad to Worse. Although it’s called From Bad to Worse, the protagonist can start anywhere on the Fortune Axis. The only rule: things need to keep getting worse and worse. These are the stories that haunt us — Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and the first 75 minutes of Dude Where’s My Car.

But are these actually the most popular stories in Western civilization, as Vonnegut theorized? There was no way to know for sure — until a few years ago.

Vonnegut’s story shapes meet science

Vonnegut first developed his Shapes of Stories theory before he wrote a single book. After reading a ton of popular novels, he pitched it as his thesis in the anthropology program at the University of Chicago in 1946. Vonnegut believed that we could learn more about a society from its stories than its pots and spears.

His proposal was promptly rejected.

So he did what all writers do now when they don’t know what to do with their lives: He quit the program and became one of the world’s first content marketers at GE, telling stories of futuristic innovation, which inspired him to start writing sci-fi novels.

In the video above, Vonnegut theorizes that “there’s no reason these shapes couldn’t be fed into computers.” So a few years ago, a group of researchers decided to do just that — using sentiment analysis via natural language processing (translation: some AI shit) to analyze nearly 2,000 popular works of fiction to see if Vonnegut’s theory about stories having universal shapes was right.

Was he right? Of course he was! He’s Kurt freaking Vonnegut. Not only was he right, but he also predicted a future in which our AI overlords would prove him right. (This whole thing is like the plot of a very meta Vonnegut novel.)

In aggregate, the arcs of the stories analyzed by the researchers matched Vonnegut’s eight shapes of stories (with some very minor differences).

How Vonnegut’s shapes of your stories can make you a better storyteller

Vonnegut’s shapes of stories aren’t just meant to be some nerdy ish you talk about with your writer friends or print out as inspiration to paste above your writing desk like a Live Laugh Love placard. They’re meant to literally be drawn — ideally on a giant chalkboard while wearing a tweed jacket and smoking a pipe. That’s because drawing the shapes of stories is a powerful way to unlock your creativity, even if you don’t self-identify as a visual learner. Do you hear that music? Oh hell yes — it’s time for a neuroscience lesson.

The physical act of drawing creates what neuroscientists call “multimodal encoding.” Basically, your motor cortex is controlling your hands and fingers at the same time that you’re engaging the planning center of your brain — the prefrontal cortex — as you think about the shape of your stories. This gives your brain myriad neural pathways to remember and analyze the structure of the story you’re telling: the motor memory of drawing, the visual memory of seeing it, or the memory of planning the story itself.

Funny enough, “multimodal encoding” is also how my two-year-old is learning the alphabet right now — by not just looking at letters, but tracing them too. It’s 3 PM on a Saturday: He’s drawing letters, I’m drawing stories, and my wife is wondering if she married a toddler.

I’m no Vonnegut, but I have made drawing stories part of my writing process — whether I’m writing personal essays, outlining my next book, working on the TV show I’m co-creating, or actually making money by consulting with a founder or brand on how to tell their story.

Storytellers far more talented and less corrupted than me do the same — just watch Christopher Nolan draw the plot of MOMENTO (and try not to swoon). Here are some steps to put this into action:

Draw the shapes of your favorite stories

I know this may sound like a middle school english class exercise, but to start, it helps to draw the shapes of the stories that you love.

Let’s really lean into the middle school vibe and examine Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the seventh and final book in the Harry Potter series. The plot seems intricate, but as the researchers found when they ran it through their NLP analysis, it’s just “Man in a Hole” over and over again. The continuous conflict and resolution keep us glued to the page.

Case in point: I bought this book the day it came out when I was 19 years old, backpacking through sunny Spain. Instead of drinking wine out of the bottle in a buzzing plaza like a normal teenager, I holed up in my hostel for 20 straight hours until I finished it — like the millennial stereotype that I am.

When you’re binging Netflix and Max this cuffing season, challenge yourself to draw the narrative arcs of the stories you love the most. You’ll start to recognize patterns. I find myself drawn to “Cinderella” narratives — the series of magical gifts creates a happy momentum that propels the story forward, and then you’re crushed as it all comes crashing down. Studying stories this way will help hone your storytelling “fast twitch” muscles, making your narrative choices more instinctual. (For a handy guide, I built an interactive tool to help you explore Vonnegut’s Shapes of Stories here.)

Work backward from the emotional journey you want your audience to go on

Do you want your audience to experience hope? Joy? Resilience? Catharsis? Horror? Different shapes of stories map to different emotions.

For instance, I’ve been writing a TV workplace comedy about a group of underdogs trying to make it in the new world of work. We want the audience to feel a sense of resilience and hope but also anxious for the fate of our heroes along the way. That means we’ll lean on the “Man in a Hole” and “Cinderella” structures. From Bad to Worse would be way too dark.

Want to create a sense of anticipation and joy? Choose Boy Meets Girl.

Inspiration and wonder? Tell a Creation Story.

Triumph and vindication? Might I recommend Cinderella.

Shellshocked? Introducing The Old Testament. (It’s very popular!)

Existential dread? From Bad to Worse, baby.

Like any rule, this isn’t perfect, but it can help you quickly get unstuck and identify the narrative arc that’s going to work best.

Map characters’ arcs against each other

I usually write short stories and essays, but lately, I’ve been working on longer works of fiction for the first time since college. (Look at me, evolving in my 30s!) And I’ve found that drawing different characters’ arcs against each other keeps me on track. Parallel shapes, for instance, can show connection — for example, in Game of Thrones, the Stark kids all go through similar Man in a Hole arcs. Intersecting points where characters meet each other while rising and falling are great moments for confrontation — think Walt and Jesse in Breaking Bad or Gatsby and Tom.

Collaboration

This is kind of obvious, but if you’re writing with other people — either on a TV show or novel or, god help you, some sort of “brand story” pitch deck with 12 different opinionated cooks in a kitchen — drawing these arcs is a great way to get everyone on the same page.

Pacing

Like most people, I overwrite first drafts, and the culprit is usually the same: I linger on plateaus for too long, basking in the awesome and awful. Mapping each scene to the shape of the story helps me figure out when I need to make cuts and get things moving. One final benefit is that once you start looking for the Shapes of Stories, you’ll see them everywhere — in your favorite shows, on Broadway, at happy hour in your best friend’s story of their wonderfully awful date. And you’ll realize there really are universal stories that unite all of us. So it goes.

Recommended Reads

The Mainstreaming of Loserdom (Tell the Bees): Internet has ruined fun.

An IVF Mixup, a Shocking Discovery, and an Unbearable Choice (Susan Dominus/NYTimes): Read the story now, watch the Netflix movie about it in 12 months.

The Expanse (James A. Corey): We all need some trashy sci-fi right now.

I’m the best-selling author of The Storytelling Edge and a storytelling nerd. Subscribe to this newsletter to get storytelling and audience-building strategies in your inbox each week.

Great text! Thank you for sharing!

This post is so great it´s the first time I save something in Substack.